“When the facts change, I change my mind.”1

What we once thought was madness we now know to be any number of medical conditions that are manageable illnesses.

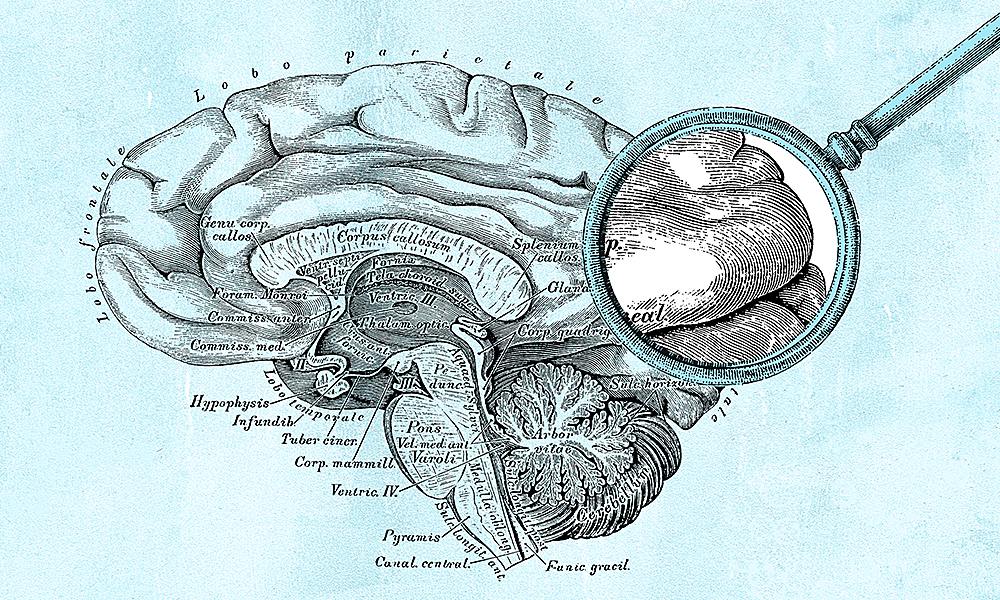

Neurological science has progressed significantly in the 21st Century,2 so it is no surprise that people question the legal system’s reliance on legal precedents that predate scientific advancement.

An article in the Daily Mail reported on the recent English decision of In the Estate of Mrs Mary Jean Clitheroe Deceased [2020] EWHC 1185 (Ch) (Clitheroe), in which the court found against a son propounding his mother’s will.

The court found his mother did not have the requisite capacity on the basis that the testator was suffering from insane delusions that impacted her testamentary capacity. There the court found against him, relying on the traditional test of testamentary capacity enunciated in Banks v Goodfellow.3 It was reported that the son was determined to appeal the decision citing that the “150-year-old test” does not reflect our modern understanding of mental capacity.

The court found that he did not satisfy the requirement that his mother had the requisite capacity when executing a number of wills, as she suffered from delusions about her daughter, his sister. He complained that reliance on this ancient legal test was at odds with English legislation crafted to recognise the complexity of cognition and the dignity of autonomy, reflected in the Mental Capacity Act 2005.4

Wills are unlike any other legal act. At common law, in all legal acts a person is presumed to have capacity until proven otherwise or as excepted under legislation. However, for a formal will that is not the case.

Where a person holds out a document to be the last valid will of a deceased person, the burden of proof is on that person to establish that the deceased person had testamentary capacity. That rule of common law has stood for hundreds of years:

“it is for the person propounding a will to satisfy the court that the testatrix was of sound mind: Waring v Waring (1848) 13 ER 715.

“A will rational on its face, executed and attested in the manner required by law is presumed in the absence of evidence to the contrary to have been made by a person of competent understanding. If however there are circumstances in evidence to displace that, the presumption will not apply and the onus is on the party propounding the will to establish that the testator was of sound mind when he executed the will: Symes v Green (1859) 164 ER 785 and Sutton v Sadler (1857) 140 ER 671.”

With regard to delusions, where it is established that the testator suffered from them, the person propounding the will bears the burden of proving that the testator was free of them or that they did not affect particular dispositions. In Smee v Smee (1879) 5 PD 84 Sir Hannen J at page 91 said:

“Unless your minds are satisfied that there is no reasonable connection between the delusion and the bequests in the wills, those who propound the wills have not discharged the burdens cast upon them, and your verdict must be against them.”5

Dissatisfied with the outcome in Clitheroe, the deceased’s son is appealing the decision, based on the rationalisation that, where medical science and technology is so advanced and gives us greater understanding of the human mind, then why are we still relying on a legal viewpoint that is hundreds of years old?

There may be some impetus for that position. In my Proctor article, ‘Banks v Goodfellow sesquicentennial – Is there anything new under the sun?’,6 I reported on the decision of Re SB; Ex parte AC [2020] QSC 139 in which the court raised query over the applicability of Banks v Goodfellow in the context that it was framed in such a way as to assume the ability to communicate, raising a question mark where a person may have mental capacity but no means by which to communicate that.

With each of these challenges to the traditional test, it may be that ultimately the courts or our legislators will recognise the advances in medical science and change their view of the law that reflects our greater understanding of mental capacity.

* Polonius in Act 2, Scene 2 of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

Christine Smyth is a former President of Queensland Law Society, a QLS Accredited Specialist (succession law) – Qld, a QLS Senior Counsellor and Principal of Christine Smyth Estate Lawyers. She is an executive committee member of the Law Council Australia – Legal Practice Section, Court Appointed Estate Account Assessor, and member of the Proctor Editorial Committee, STEP and Deputy Chair of the STEP Mental Capacity SIG Committee.

Footnotes

1 Attributed to Paul Samuelson, who was awarded the 1970 Nobel Prize in economics.

2 scientificamerican.com/article/10-big-ideas-in-10-years-of-brain-science.

3 (1870) LR 5 QB 549, 565 per Cockburn CJ.

4 scie.org.uk/mca/introduction/mental-capacity-act-2005-at-a-glance#:~:text=The%20Mental%20Capacity%20Act%20(MCA)%202005%20applies%20to%20everyone%20involved,vulnerable%20people%20who%20lack%20capacity.

5 At [161]-[162] In the Estate of Mrs Mary Jean Clitheroe Deceased [2020] EWHC 1185 (Ch).

6 QLS Proctor, posted 4 September 2020.

Share this article